The following are the results of the queries I completed on each corpus. Please feel free to follow along by pasting the query terms into the code. Be sure to load in the correct corpus before beginning the analysis.

Latin America Model Results

The first query I performed on the corpus attempted to investigate terms of the female gender by searching “woman” + “girl”. Interestingly, the closest word along this vector is “jeep” with a .77 similarity, presumably related to military equipment. The next several terms depict violence and crime. “Jail” and “killed” register at a .68 similarity. “Cell”, “traitor”, “survivor”, “demonstrators”, “burned”, and “shot” all have a .65 similarity to the queried “woman” + “girl”, depicting images of violence during this period.

Figure 1. Report on Argentina armament. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947, The American Republics, Volume VIII. Editors: Almon R. Wright and Velma Hastings Cassidy (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1972), 198.

Figure 2. Unrest in Argentina 1945. Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, The American Republics, Volume IX, eds. David H. Stauffer and Almon E. Wright (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1969), Document 287.

Figure 3. Unrest in Panama 1949. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, The United Nations; The Western Hemisphere, Volume II, eds. Ralph R. Goodwin, John P. Glennon, David W. Mabon, and David H. Stauffer (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), Document 433.

Figure 4. Unrest in post-1954 Guatemala. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, American Republics: Central and South America, Volume VII, eds. Edith James, N. Stephen Kane, Robert McMahon, and Delia Pitts (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1988), Document 46.

In attempt to strengthen the results of female-related terms, I then removed terms of the male gender from the search terms (“woman” + “girl” - “man” - “boy”). This presented much clearer terms of disobedience and violence, although the term similarity was much lower in strength. In relation to death, “buried” has a .50 similarity. Terms of unrest such as “streets” and “rioters” showed a .49 similarity, with “arrests” having a .47 similarity. Weapon-related terms such as “shots” (.50), “machetes” (.48), and “sniper” (.47) are present. Despite having lower similarity coefficients, the terms appear to relate the closest to the queried vector.

Figure 5. Unrest in post-1954 Guatemala. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXXI, South and Central America; Mexico, eds. David C. Geyer and David H. Herschler (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 2004), Document 75.

In both corpora, traditional gender roles appeared frequently in regard to women. In order to dive deeper into these roles, I first queried “woman” + “mother”. Aside from some family-related terms, the results included more themes of violence. “Murdered” (.62), “escaped” (.59), “assailants” (.59), and “arrested” (.57) show similarity to the queried pair. These traumatic themes are also present when searching for similarity to “woman” + “wife”. In this query, “shouted” (.61), “deserted” (.61), and “prison” (.61) add to the depiction of individuals being involved in events with mistreatment and criminal implications. To combine the three terms of involved with traditional domestic roles, “woman” + “wife” + “mother” produced similar results to the previous queries. These queries interestingly show rates of similarity to occupations and places of work such as “restaurant” (.68), “poet” (.66), “newsman” (.65), and “diplomat” (.60). These are likely based on other roles being discussed in similar contexts or proximity to the “wives” and “mothers” as shown in the example below. Therefore, I removed men from the equation (“woman” + “wife” + “mother” - “man”). This query produced almost the same results apart from the term “daughter” which contains a .58 similarity.

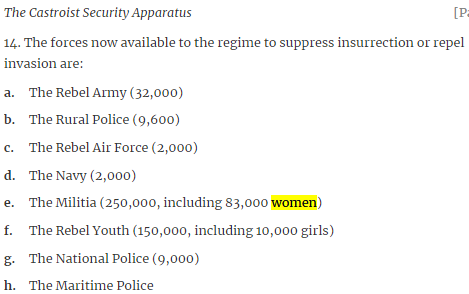

Figure 6. The status of the Castro regime. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume X, Cuba, January 1961–September 1962, eds. Louis J. Smith (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1997), Document 271.

Figure 7. Unrest in Argentina. Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945, The American Republics, Volume IX, eds. David H. Stauffer and Almon E. Wright (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1969), Document 290.

But are these results simply the product of Latin American diplomats’ interpretations of the region at the time? Are these the general inferences made on the entire population, products of the policies and concerns over the region, or are they gender specific? To investigate such questions, I conducted an investigation into the male gender. As before, I first queried basic terms of gender, “man” + “boy”. This query results in terms depicting roles or positives descriptors. Men are described as “politician” (.67), “friend” (.64), “statesman” (.63), “diplomat” (.62), “collaborator” (.61), and “hero” (.60). In addition to these esteemed titles, descriptions of “knowledgeable” (.62) and “undisturbed” (.62) are present, with an interesting “hated” (.60) included. Upon removing terms of the female gender, (“man” + “boy” - “woman” - “girl”) resulted in terms that vaguely relate to political planning or bureaucratic proceedings. “Dictate” (.30), “guidance” (.28), and “solutions” (.27) present some of the ambiguous language resulting from this query, but it is important to note that these results are very weak and do not demonstrate a strong relationship to terms of the male gender, although they do appear to relate to the professional terms resulting from the original query in this model. To strengthen the vector associated with terms of male gender, I searched all corpus-relevant terms of the male gender, “man” + “boy” + “men” + “boys”. Of note are the professional position of “soldier” (.64) and the Spanish term for foreigners to Latin America, “gringos” (.66).

Figure 8. Instability of Mexican economy. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, The United Nations; The Western Hemisphere, Volume II. Editors: Ralph R. Goodwin, John P. Glennon, David W. Mabon, and David H. Stauffer (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 409.

Figure 9. Leadership change in Nicaragua. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, American Republics: Central and South America, Volume VII. Editors: Edith James, N. Stephen Kane, Robert McMahon, and Delia Pitts (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1988), 108.

Figure 10. Relationship with Castro regime. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume VI. Editor: John P. Glennon (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1991), 268.

I also explored traditional gender roles within the corpus. Whereas the female-related queries explored traditional roles that were present in the corpus, I queried traditional roles in order to discover terms used in similar contexts. First, I searched for “man” + “father”. As in the first query for male gender, this query presented professional roles, some similar to the first query but with stronger coefficients, and also new terms such as “lawyer” (.77), “leader” (.64), and “dictator” (.64). A search into another traditional role (“man” + “husband”) resulted in some similar roles, but also a few positive terms such as “admirer” (.63) and “ambition” (.60). Lastly, a search combining these roles (“man” + “husband” + “father”) did not produce any novel results, apart from adding a professional title of “newspaperman” (.62).

As shown in figure 1-7, the terms that are most closely related to female terms of gender or gender roles are often not near or about women. More often than not, these terms are in proximity or are in regard to political dissidents. Based on these observations, it appears as though women are regarded as an “other” or a form of grouping. When describing groups targeted by violence or taking part in dissent, “women” or “girls” are used as a subcategory to the groups participating in or facing the repercussions for political dissent.

Please note that other terms of gender, such as “female” and “male” were included in some preliminary queries, but they skewed the results. These terms were likely not used in general communication when discussing subjects of policy or colleagues.

European Model Results

Although the corpus concerning Latin America presented interesting results depicting civil unrest, could this be an artifact of the period in general? Could it be how all policy planners saw social relations during the period? To determine the unique quality of the Latin American corpus, I queried the same terms on a corpus composed of FRUS documents regarding Europe from the same period. If you are following along in the code, please be sure to load in the European corpus by redirecting the file path.

The first set of queried terms, “woman” + “girl”, resulted in very different themes than shown in the Latin American corpus. Terms closest to the queried set depicted familial relations, such as “daughter” (.75) and “wife” (.71). Also in these results were terms relating to agriculture: “lamb” (.71), “mule” (.69), and “chicken” (.68). Of course, there are several other intriguing results such as “sack” (.73), “knife” (.69), “altar” (.68), and “tomb” (.68). To strengthen this vector, I searched the terms “woman” + “girl” + “women” + “girl”. Similar to the previous corpus, “assaulted” (.76) most closely related to the queried terms. Many other results pertain to an event or an exhibition of sorts. “Songs” (.76), “singers” (.76), “singer” (.74), “crowd” (.74), and “marched” (.74) all appear to be quite similar to the terms of female gender. Removing male gendered terms from a female vector, I queried “woman” + “girl” - “man” - “boy”. This produced an interesting series of nouns: “guardians” (.43), “mobs (.42), “rebuttals” (.41), “carelessness” (.41), “killings” (.39), “verdicts” (.39), and “acquittal” (.38). These terms appear to be related to legal jargon.

Figure 11. Khrushchev conversion with Harriman. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Volume X, Part 1, Eastern Europe Region; Soviet Union; Cyprus. Editors: Ronald D. Landa, James E. Miller, David S. Patterson, and Charles S. Sampson (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1993), 75.

In this corpus, roles associated with the family are very closely related to the originally queried terms. To explore these vectors further, I first queried “woman” + “mother”. Many other terms of familial relations fall along this vector, such as “daughter” (.79), “wife” (.77), “brother” (.73), “child” (.72), “husband” (.69), “son” (.68), and “family” (.66). The results of the “woman” + “wife” + “mother” query are predictably the same, all relating to familial roles.

In comparison with the basic female gender search, a basics examination of male-gendered terms provided very different results. Searching “man” + “boy” produces a series of career titles: “physician” (.73), “bodyguard” (.72), “statesman” (.69), “politician” (.67), and “soldier” (.66). To strengthen the vector, I searched “man” + “boy” + “men” + “boys”. Many similar terms appeared, plus some adjectives: “tall” (.71), “young” (.68), and “crazy” (.67). Removing the female gender from the vector ( “man” + “boy” - “woman” - “girl”) produced a very long list of verbs which include “outweighed” (.36), “advancing” (.29), and “reorganizing” (.29), and some nouns such as “standpoints” (.33) and “disengagement” (.28). Please note that these results of the previous query were not particularly close in relation to the search terms.

Figure 12. Discussion on the UN. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, Eastern Europe; Soviet Union; Eastern Mediterranean, Volume VIII. Editors: David M. Baehler, Evans Gerakas, Ronald D. Landa, and Charles S. Sampson (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1988), 200.

Finally, I searched for traditional male roles within the corpus. First, “man” + “father” produced several career titles such as “diplomat” (.72), “physician” (.70), “reverend” (.69), and “teacher” (.67). Searching “man” + “husband” showed almost the same results, plus “actor” (.66). The same held true for the query “man” + “husband” + “father”.

Terms associated with women in Europe seem to largely point to the domestic sphere, with “daughter” and “wife” being the most strongly associated terms, and terms of agriculture also being closely related. Roles are extremely important for both genders in the European corpus, with female-related queries highlighting familial roles, and male-relate queries emphasizing professional roles.

These results are discussed further in the conclusion. To read more on how historians have analyzed gender in foreign relations, please see the brief literature review.